The Thirteenth YearThere's a lot of silly superstitions around, one of which regards the number 13 as unlucky, leading to irrational but septasyllabic triskaidekaphobia. Tall buildings are built with floors numbered up to 12, then 14 and beyond; it must play havoc with the design engineers. According to Shyam Sunder Gupta, in 1993 the prestigious British Medical Journal solemnly stated “Friday 13th is unlucky for some. The risk of hospital admission as a result of a transport accident may be increased by as much as 52 percent. Staying at home is recommended." Gupta gives numerous reasons for the belief, including the fact that Knights Templar were arrested and slaughtered by French King Phillip IV on Friday August 13th, 1307; and adds some interesting mathematical quirks connected with the number. Is this 13th year of the 21st Century an unlucky year? I would say so. Although several years in preparation and with many a warning of its advent, this is the year that the appalling level of deliberate, detailed government surveillance of the population has finally come into the light of day, and that marks a highly sinister new chapter in our history. Response from its spies is that “nothing illegal has been done” and that may be quite true, though it needs a paragraph or two of explanation to make it so. Very obviously, for the Feds to scan every piece of snail mail, every email and every phone call is a gross violation of Amendment 4, and isn't that the supreme law on the subject? Such spying makes us "insecure" and has no "reason" in the intended sense of specific suspicion pointing my way, nor any specific "warrant" authorized by a court after a public hearing, nor any "oath or affirmation" to support a "probable cause" of wrongdoing.

Reaction of this and other governments to the disclosures by Edward Snowden have, as to the earlier ones by Bradley Manning, been furious, ominous and scary. On receiving flimsy evidence that he might have been smuggled out of Moscow by President Morales of Bolivia, who had spoken of him sympathetically, France and Spain denied his aircraft fly-over privileges on July 2nd, so it had to land in Vienna to be searched. This was evidently done on the say-so of Barack Obama; four governments cooperated, grossly to insult one of their own! So far, so breathtaking. Snowden was then marooned in Sheremetyevo until August 1st, when the Russians gave him a year's residency; Obama was then so enraged as to cancel a planned formal visit to Russia and switch it to Sweden, where he can be sure of a welcome. That's the country whose government, recall, has declined to promise that if Julian Assange were to go there for trial on a trumped-up rape charge, he would not be extradited to the US. More recently, in its fury at the whistleblowing, the FedGov has bullied the Guardian, whose reporter Glenn Greenwald had publicized what Snowden said, in two ways. Its reliable friends in the UK government intercepted David Miranda at Heathrow for an unprecedented nine hours of interrogation, while in transit from Berlin to Rio in his homeland of Brazil, and stole some of his property. Miranda's crime had been to work with Greenwald. Evidently, the lesson here is that if Putin can use the “limbo” of a transit lounge to deny that someone wanted by the US is available to him, Obama (or Cameron) can use a transit lounge for an opposite purpose. The ambiguous legal status of a transit area is now being used to bypass any of the few remaining restrictions on government power; travel across government borders only at your own risk. This “half-world” twilight was well identified in this Guardian Editorial. Then Her Majesty's Government issued an oral threat of legal action against the newspaper, as a result of which it agreed to destroy a perfectly good laptop containing the secret files, while observed by a government bureau-rat. These are unmistakable signals that governments do not expect the media to bring them any embarrassment, but rather to serve only as spokesmen for official propaganda. They care little about how many of their own laws they break, but react savagely when their misdeeds are exposed to public view. The parallel with 1930s Germany is truly eerie. Orwell, remarkably, foresaw most of this half a century ago; he must have understood rather well what government is all about. But there it is: for as long as government continues, the freedom to live one's own life privately and in one's own way is finished. The thirteenth year of this present century isn't done yet, but already it marks the end of an epoch. How about the thirteenth year of the last one? The Federal Reserve Act or the first Income Tax Act both blighted America's history in that year. The first of those was Congress' establishment of a central bank under its control (since whatever it sets up it can certainly take down) from which the Feds can, at least, borrow money that doesn't necessarily exist at the time of borrowing. Central banks having been abolished in America twice before, the conspirators were careful in 1913 to give the Federal Reserve the appearance of being a private club, and indeed the association of its member banks do very nicely out of the deal. It has wrought such havoc in its first century that after gaining about 0.5% in purchasing power annually during the previous one (due efficiency gains as a relatively free market did its good work), it has lost 98.5% of that power ever since. But government now has the ability to “create money” at will, and this year it has been counterfeiting $85 billion per month. That's a trillion bucks a year – as much as all they collect as “income tax”--made to look smaller. 1913 therefore marked the end of honest money. The blight of the income tax is even more obvious, for it steals one work day from every week of work performed in America and hands the loot over to the FedGov ready to spend any way it deems most likely to win it votes. It's never been enacted by statute law, but is enforced anyway as if it had, by the action of the Judicial Branch as noted above. Not only does it savage our ability to provide for ourselves, it gives government generous access to a whole range of private information, now outclassed only by the ubiquitous NSA spy machine. I can't tell you that the year 1813, one century earlier yet, was a landmark in US history. But in 1813 America was in the midst of a war. Why? What did a free society (that's what it was supposed to be) have to do with war? Was it a defensive war, and if so, why was the government waging it? If it had been defensive, to fight the War of 1812 would have accorded with the Constitution; one of its main purposes had been to socialize defense. So in that case the blood let in this nasty little fight (not to be compared with the river of it that flowed from the big one, between France and Russia) would have clarified that while at that time most aspects of life were left in private hands, defense was an exception where collectivism was alive and flourishing. But it wasn't defensive. The Brits can fairly be said to have begun it, by kidnapping American sailors on American merchant ships, on the high seas and in British ports for the purpose of trade. The Royal Navy was short of men in its war against France, and it seemed a quick fix to grab some sailors from the ships of those no-account, uppity ex-colonials. But then came the critical error: Congress reacted by authorizing its government navy to retaliate. This followed its action in using the US Navy and Marines – very effectively – to counter piracy off the North African coast, which had been going on for centuries. “Error”? Yes, it was a major one, if we suppose the young America was a free country; for in the coming free society, merchant sailors will arrange their own defense and build the costs in to their product prices. But it was no error if we recognize that it was just another tax farm, with a century or two to grow before swinging influence among the world of nation states. A quarter century earlier, government had been established, complete with war-making powers. So it wasn't a matter of bad luck, that such a promising new society deteriorated into a global bully, complete with massive military power, a tight grip on its own fiat currency, and unprecedented machinery for spying on and so controlling its “own citizens.” It was a matter of bad judgment – the foolish mistake of supposing government to be desirable or necessary. |

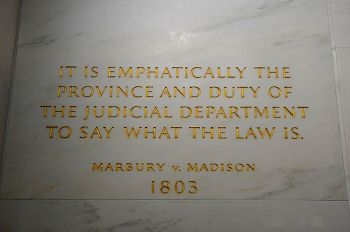

If laws have been written in contravention of Amendment 4 they are void, so the claim about “nothing illegal” begins to totter. But wait, they're not done. Early in the Republic's life, the power to decide what is and is not Law in this country, including the power to decide what the Constitution means (as if it were written in Arabic) got

If laws have been written in contravention of Amendment 4 they are void, so the claim about “nothing illegal” begins to totter. But wait, they're not done. Early in the Republic's life, the power to decide what is and is not Law in this country, including the power to decide what the Constitution means (as if it were written in Arabic) got